The Battle of Pavia (1525): the moment that changed Europe and the birth of modern warfare

The Battle of Pavia was one of the pivotal events in European history. It marked the culmination of the conflict between the two major powers of the time: Charles V, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire—who reigned over Spain, Naples, Sicily, and Sardinia and controlled the Netherlands, Franche-Comté (west of modern-day Burgundy), and the Austrian Habsburg territories—and Francis I, King of France, who controlled the Duchy of Milan.

Emperor Charles V

The emperor sought to take control of Milan and Burgundy to completely encircle France, while Francis I aimed to conquer the Kingdom of Naples and counter the imperial threat.

Habsburg Empire of Charles V in 1544

In October 1524, Francis I led his powerful army into Italy, determined to reconquer Lombardy, which had recently fallen to Spanish imperial forces. The imperial army, seeking to avoid open battle against the numerically superior French, abandoned Milan and retreated to Lodi, leaving a strong garrison in Pavia. This strategy aimed to slow the French advance and buy time to assemble a new army.

The defence of Pavia was entrusted to Antonio de Leyva, one of Charles V’s most loyal commanders, who lead nearly a thousand Spanish troops and five thousand German Landsknechts. Rather than pursuing the retreating imperial forces, Francis I decided to lay siege to Pavia, confident that the city would fall easily. The siege continued from October 1524 to February 1525, until the two armies finally clashed in a battle lasting no more than two hours.

Portrait of King Francis I

The result was catastrophic for France: Charles V achieved a decisive victory, and Francis I was captured after falling from his horse, marking a turning point in the war.

The surrender of King Francis I

The battle confirmed the skill of the Spanish imperial commanders and their arquebusiers against the less effective French noble knights, still rooted in feudal warfare. The key to Charles V’s victory was the technological superiority of the Spanish infantry, equipped with firearms that were state-of-the-art for the period. These new weapons transformed warfare, bridging the Middle Ages and the Modern Era.

The Battle of Pavia, King Francis I and his knights

From Pavia to the present: war, technology, and power then and now

The Battle of Pavia was crucial because it marked the dawn of a new era. Although gunpowder weapons existed earlier, the arquebus was the first firearm to be used systematically on the battlefield and the first practical, shoulder-fired personal weapon to have a decisive impact.

The introduction of the arquebus shifted warfare away from the exclusive domain of the nobility and armoured aristocracy toward infantry drawn from the common people.

Our twenty-first century has much in common with the age of the Battle of Pavia: the rapid spread of printing then mirrors the internet today; new technologies are once again reshaping warfare, just as firearms did in the sixteenth century and as drones do now; and even seemingly timeless elements persist, such as the use of mercenary soldiers—once the Landsknechts, today operating under different names as PMCs (private military companies) such as Wagner, Blackwater, and Aegis Defence, still employed and paid by states.

Finally, both periods are marked by a redefinition of the global balance of power: then among European monarchies, and today among the United States, Russia, and China.

Why the Duchy of Milan was something of a French “obsession”

Louis XII and Francis I of France focused on the Duchy of Milan for dynastic, strategic, and economic reasons. Their claims stemmed from descent from the Visconti family, while Milan’s location was crucial for controlling northern Italy, enhancing French military prestige, and dominating the wealthy Lombard trade routes. At the time, the Duchy of Milan was one of the richest and most populous states in Europe, providing vital resources to finance warfare.

Among the eleven dukes who ruled Milan between 1395 and 1535, two were French: Louis XII (1499–1512) and Francis I (1515–1521).

Louis XII claimed the duchy as the grandson of Valentina Visconti, wife of Louis of Orléans, asserting the legitimacy of French rule over Milan. Valentina Visconti was the daughter of Gian Galeazzo Visconti, the first Duke of Milan, and Isabella of Valois, who married Louis I of Valois-Orléans, brother of Charles VI, King of France, who reigned for forty-two years (1380–1422).

When Louis XII died of gout on 1 January 1515, at the age of fifty-three and without direct male heirs, the French crown passed to the twenty-one-year-old Francis I of Valois-Orléans-Angoulême. As Louis XII’s son-in-law—having married his daughter Claude—Francis promptly renewed hostilities over Milan. Like his predecessor, he believed the Duchy was rightfully his, as a family inheritance through Valentina Visconti.

What makes this particularly intriguing is the fact that, from the outset, dynastic succession to the Duchy had been based on the principle of legitimate male primogeniture—a system that had already been firmly established in Milan during the period of the Visconti lordship.

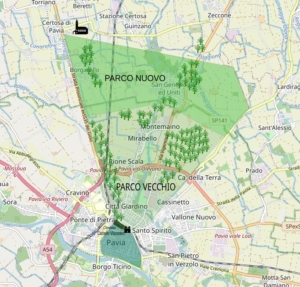

Venues of the Battle of Pavia – Walking through history

Venues of the Battle of Pavia – Walking through history

The Pavia Castle and the Castle of Mirabello, located today within the Parco Visconti, were key sites during the battle. At the time, the area around Mirabello served as hunting grounds.

Castle of Mirabello

The Castle of Pavia

For further information about the exhibition “Pavia 1525”, open until 24 February 2026, please contact me.