When Albert became Einstein

Discover Albert Einstein’s formative years in Milan and Pavia, where science, music, and innovation shaped a young genius

Albert Einstein’s formative years in Milan and Pavia represent a crucial yet often overlooked chapter in his life. Through his correspondence, we gain direct insight into his friendships, intellectual influences, and daily environment, as well as into the Lombard cities where he lived during the years that shaped his scientific thinking and personal outlook.

In 1952, in a letter to Carl Seelig—the Swiss writer and Einstein’s first biographer—Albert recalled that his parents “were divided between Milan and Pavia [the site of the production plant]”. This brief statement situates the Einstein family within the industrial geography of northern Italy and highlights the importance of Lombardy in Albert Einstein’s early development.

Italy, industrialisation, and the Einstein family

The electrotechnical activity of the Einstein family began in Munich in the early 1880s and later moved to Italy, at a time when the country was undergoing rapid transformation. Following the Second Italian War of Independence, Italy was unified under the House of Savoy in 1859, with Venice annexed in 1866. The creation of a modern nation-state led to major investments and to the first phase of industrialisation, financed by banks and insurance companies.

Hermann Einstein, Albert Einstein’s father (1847 Buchau -1902 Milan)

In 1894, Albert Einstein’s family—his father Hermann, his mother Pauline Koch, and his sister Maja—together with the family of his uncle Jakob Einstein, settled in Milan.

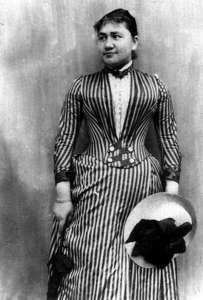

Pauline Koch, Albert Einstein’s mother (1858–1920)

Albert was fifteen years old, at a decisive moment in his intellectual and personal growth. Although he was enrolled at the Swiss Federal Polytechnic in Zurich (ETH), where he would graduate in 1900 and where his companion Mileva Marić lived, he spent long periods between Milan and Pavia. During these years, he became deeply immersed in the social and cultural environment of the Lombard industrial bourgeoisie, beginning with his close friend and future collaborator Michele Besso and extending to a wide and influential network of relationships.

This move offered Hermann Einstein and his brother Jakob the opportunity to play an even more active role in the electrification of a country to which they had already been contributing since 1887. In Munich, the company J. Einstein & C., founded by Jakob Einstein and later joined by Hermann, employed up to two hundred workers. At the same time, the Einstein family installed electrical systems in several small Italian towns from as early as 1887.

They brought with them their technical expertise and know-how. Their enterprise thus became intertwined with the industrial history of Italy—a country that was not yet thirty years old, having been unified only in 1861, and which still represented a land to be developed and shaped. The houses in which the Einstein family lived, both in Milan and in Pavia, had previously been occupied by patriots who had played a prominent role in the unification of Italy and had been made available to them. This circumstance places the Einsteins’ presence within a broader historical and political perspective. Indeed, the influence of the revolutionary period of the Risorgimento, which led to Italian unification, was still strongly felt at the end of the nineteenth century, as the Italian ruling class had been forged within this shared ideal.

The Einstein family’s presence in Milan took shape in the period immediately following the Second Italian War of Independence, which led to the unification of Italy under the House of Savoy in 1859, later completed with the annexation of Venice in 1866. The birth of a modern nation-state brought with it major investments and the beginning of an industrialisation phase financed by banks and insurance companies.

Milan at the heart of European innovation

The 1880s marked a technological turning point across Europe. Electric street lighting began to replace gas lighting in major cities, and a new professional community of electrotechnical engineers emerged. In Milan, the Polytechnic was founded in 1863, eight years after the establishment of the ETH (Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule) in Zurich. In 1872, Giovanni Battista Pirelli, a graduate of the Milan Polytechnic, founded Italy’s first tyre manufacturing company. Two years earlier, Ulrico Hoepli, a Swiss native of Zurich, had established the publishing house that still bears his name, supporting Italy’s scientific and industrial development through technical and specialised publications. The very young Albert Einstein frequented the Hoepli bookshop and studied electricity using textbooks published by this pioneering press.

This environment offered Hermann Einstein and his brother Jakob the opportunity to play an increasingly active role in the electrification of a country to which they had already been contributing since 1887. In Munich, the company J. Einstein & C., founded by Jakob Einstein and later joined by Hermann, had employed up to two hundred workers. At the same time, the family installed electrical systems in several small Italian towns. They brought with them technical expertise and industrial know-how, and their enterprise became intertwined with the industrial history of Italy—a country that was not yet thirty years old and still undergoing rapid transformation.

From Frankfurt to Pavia: a young mind takes shape

In 1891, the Einstein family participated in the Frankfurt Electricity Exhibition, organised to evaluate competing systems of electric lighting and power transmission. For the twelve-year-old Albert, this was a formative experience: it was here that he became fully aware of the technological world that surrounded his family.

On 14 March 1894—Albert’s fifteenth birthday—the Einstein family founded a new company in Pavia, specialising in the construction of dynamos and direct and alternating current motors, power transmission systems, arc lamps—lighting devices based on the luminous emission of an electric arc—and other electrical equipment. It was also involved in the transmission of electrical energy to power direct current machinery and to provide public lighting for several cities in Lombardy, Piedmont, and Liguria. The company employed approximately eighty people and was headquartered in Milan.

The 16-year-old Albert Einstein

In 1895, at just sixteen, Albert worked in his uncle Jakob’s office in Pavia, surrounded by Polytechnic-trained engineers. He gained hands-on familiarity with electrotechnical problems and consulted specialised scientific journals. This environment, combined with his family’s confidence in his abilities, led him to apply to apply in October 1895 to one of Europe’s most prestigious institutions, the Swiss Federal Polytechnic (ETH) in Zurich—despite not yet meeting the age requirement for the entrance examination and having not completed his secondary education.

Academic networks and cultural life

A decisive influence came from Galileo Ferraris, one of the founders of modern electrotechnics, who provided Albert with a letter of recommendation to attend the courses of Professor Heinrich Friedrich Weber at the ETH (Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule). Recently rediscovered, this letter—written by Einstein himself in August 1895—is the earliest known document in his hand. It is written on the letterhead of the family company and bears the address of the Einsteins’ first Milanese residence, next to the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II.

Jakob Einstein also maintained high-level connections with the University of Pavia even before the company formally settled there. As a result, Albert’s adolescence unfolded not only within an engineering milieu but also within a rich academic environment. Since the fourteenth century, the historic academic centre of Lombardy had been the University of Pavia, founded in 1361 when Milan was still a duchy under the Visconti family. It is Italy’s third-oldest university. By contrast, Milan’s numerous universities were all founded in the twentieth century, beginning in 1921.

Albert Einstein playing the violin, 1927

Beyond science, Milan nourished Einstein’s artistic sensibility. A gifted violinist, he performed in both Pavia and Milan, where the elite Quartetto Society (Società del Quartetto), had been founded in 1864. In letters to Mileva Marić, his future wife, and to his friend Marcel Grossmann, Einstein described music as essential to his emotional balance, famously noting that “musical relationships prevent me from becoming acidic”.

Einstein was also an enthusiastic hiker and mountaineer. He climbed the Säntis near Zurich, explored the mountains around Lake Maggiore, and even walked from Voghera to Genoa across the Apennines to visit his maternal uncle—experiences that reflect his love of nature and independence of spirit.

Milan, electricity, and scientific prestige

The interaction between engineering, academia, finance, and politics in Milan was fostered by the Istituto Lombardo, founded by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1797. Its first president was Alessandro Volta, inventor of the electric battery. The Institute’s library, one of the most advanced in Europe, became a crucial research space for Einstein during his Milanese stays.

On 26 December 1883, Milan inaugurated the first thermoelectric power station in Europe, near Piazza del Duomo. The Edison dynamo installed there and illuminated Teatro alla Scala during a performance of La Gioconda by Amilcare Ponchielli, making Milan the first European city with a fully organised public electric lighting system.

Einstein accessed the Istituto Lombardo’s restricted library thanks to Giuseppe Jung, uncle of Michele Besso. Decades later, in 1922, Jung proposed Einstein for election as a foreign member of the Institute, recognising that long before his global fame, Einstein was already esteemed for his fundamental contributions to physics.

The end of an Italian chapter

In October 1902, Hermann Einstein died in Milan and was buried at the Monumental Cemetery. Albert, then twenty-two, was working at the Swiss Patent Office in Bern. With his father’s death, a deeply formative Italian chapter came to an end—yet the intellectual, cultural, and human foundations laid in Milan and Pavia would continue to resonate throughout Einstein’s life

For further information, please contact me.